Introduction

As is the case with many gemstones, tanzanite (Fig. 1) has a colorful and intricate geological as well as human history, influenced by politics, economics and in many instances, a fair share of coincidental events. Although our emphasis is on geology in this tanzanite series, we cannot do justice to the stone without discussing the remarkable events that led to its discovery and mining.

(Photo: R. Scheepers / AFGEM 2002 -Block C)

More often than not, the discovery of a gemstone is shrouded in controversy. It is no different for tanzanite. Usually different variations on the discovery of the gemstone are put forward. What is clear from the various accounts on the discovery of tanzanite, a combination of curiosity, hope of commercialization, input of capable gemstone experts, identification, naming and marketing followed in a chain of events that saw the emergence of the gemstone with the formal name of tanzanite in 1967.

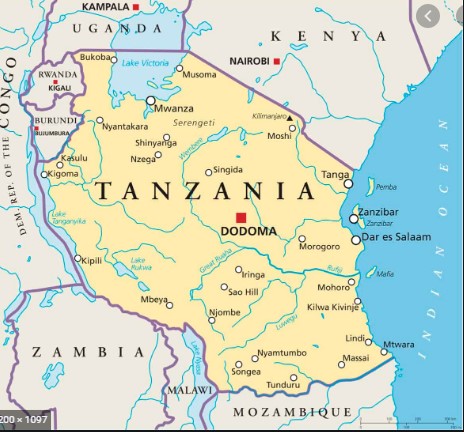

Location.

The gemstone now known as tanzanite is named after the country that was formed on 26 April 1964 by uniting Tanganyika with Zanzibar to create the United Republic of Tanzania (Fig. 2).

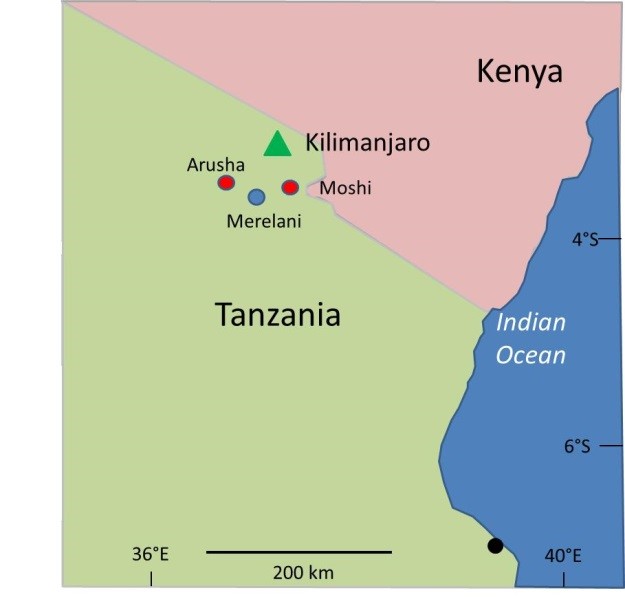

The closest town to where tanzanite was discovered is the town of Merelani (sometimes spelled Mererani) in the Northeastern part of the country. The largest regional towns are Arusha and Moshi (Fig. 3). To get to Merelani you have to travel from Kilimanjaro airport for about 18 kilometers across the lava underlain Sanae plains (Fig. 4).

Discovery.

What follows is a likely sequence of events that led to the discovery of tanzanite, based on knowledge of the local area obtained over 18 years in the country, local traditions and logistics at play. It is somewhat dramatized to add affect to the importance of the various role players in the eventual introduction of a magnificent gemstone to the world.

Masai herdsmen roamed the Sanae plains and Merelani hills for centuries. They were well aware of the presence of brown coloured stones that turned a beautiful violet or blue when lightning started bush fires that heated the stones or when campfires were coincidentally made upon the stones. Approximately 8 years prior to the official discovery of tanzanite, Dr. John Saul outlines that in the magazine GEM COLLECTOR an unverified source reported that gem quality Zoisite from an undisclosed locality was submitted to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 1959. At this time Zoisite from the Longido Zoisite – Red Corundum-Ruby deposit closer to the Tanzania/Kenya border was known. According to Saul in the same reported reference, a Polish refugee called George Kruchuk, found gem quality Zoisite in the area in 1962, but did not follow up on the find as the colour of stones found was not deemed to be impressive. For the Masai herdsman the stone had no real practical value as it is relatively soft, but it was sometimes used in beading. Besides, there was no market for it!!

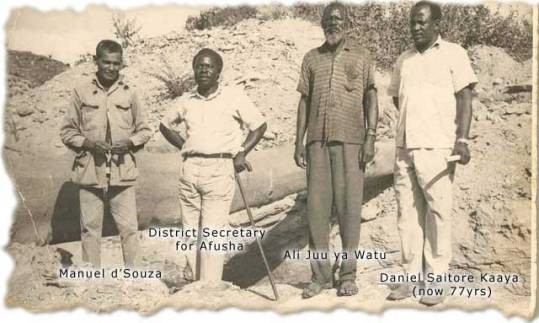

A Masai warrior who very well knew the commercial value of gemstones convinced Daniel Saitore Kaaya (Fig. 5) (who was a village elder), to mention the existence of the stones to a local gypsum miner, Jumanne Ngoma, in January 1967, while the latter was exploring in the Merelani area. Ngoma apparently had given his first few pieces of the blue mineral away and unfortunately for him it took him several months to return to the area and peg-out a claim.

Fig. 5: Photo of Manual de Souza at a tanzanite claim. Also included are Daniel Saitore Kaaya and Ali Juu ya Watu (an important role player and the man after which the main tanzanite bearing zone is named). -(Photo Source Skara Jewels Website.)

Several months later mr. Ngoma once again returned, this time to find three men digging in what he claimed was his pegged-out area. The men insisted that they were mining a legally pegged claim belonging to a certain Manual de Souza. This was confirmed to mr. Ngoma by Mining Officials from the nearby town of Moshi. De Souza proved that he had received the official mining rights two months earlier, illustrating the importance of acting in a timely manner.

It is important to note that the Tanzanian Government recognizes mr. Ngoma as the true discoverer of tanzanite. Mr. Ngoma was awarded the Order of the United Republic (of Tanzania), second class, by then President Jakaya Kikwete in 2015. On 12 April 2018 President John Magufuli awarded mr. Ngoma with an amount equivalent to US$ 44 000. In the photograph below (Fig. 6) mr. Ngoma is seen with president Dr. John Magufuli.

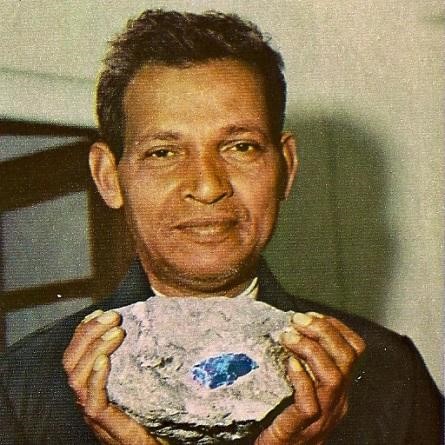

The role of Manual De Souza cannot be over-emphasized (Fig. 7). An excellent firsthand account of the role of De Souza is provided by Dr. John Saul in the Summer 2007 edition of InColor Magazine pages 15 – 17.

(https://www.gemstone.org/incolor/Incolor05/index.html#17/).

As Dr. Saul and his sons are “on the ground” professionals we emphasize their account of the unfolding of events. A summary is provided below:

During the Easter weekend of 1967 Manuel de Souza, a tailor from Goa in India and a keen prospector, opted to miss a family reunion party and went on a prospecting trip to the Merelani hills South West of Arusha, most likely based on accounts of the presence of a blue stone by mr. Ngoma or a Tanzanian miner by the name of Ali Juu ya Watu or simply following his own curiosity. He was most likely led to the site by Maasai tribesmen. Based on John Saul’s account as reported in GEM COLLECTOR the events unfolded as follows:

In De Souza’s words as reported by Dr. John Saul: “At around midday, I saw a blue transparent gem shining on the ground. At first I thought I had found Sapphire, however I tested its hardness and realized it was too soft to be Sapphire. That night, on my return home, I cross-referenced my discovery with my gemstone book, and decided that the closest match was that of Olivine”. Of course it was not Olivine. (An interesting twist to this error of De Souza is that nowadays one of the minerals being sold as tanzanite is synthetic forsterite (which is a member of the Olivine Group of minerals)). De Souza proceeded to register a claim (evidently on the 25th July 25 1967, with an amendment added to it on 17th April 1968 (GEM COLLECTOR).

Events then followed the typical unexpected, coincidental and spur of the moment time line so typical of the discovery of many great gemstones. These are best described in the words of Dr. John Saul (an MIT-trained geologist and gem dealer in Nairobi) as reported in GEM COLLECTOR and in an interview of November 2019 on YouTube:

“I met Manuel on a visit to Tanzania and at that time he had labelled his gems (later tanzanite) as Dumortierite. So I sent the gemstones to my father, Hyman Saul, who was the Vice President (Commercial) of Saks Fifth Avenue in New York.

He took them across the street to the G.I.A. (Gemological Institute of America (GIA) who confirmed them as belonging to the Zoisite Group of minerals.” There are also reports that the first identification of the stones as Zoisite was in fact done by the Geological Survey of Tanzania Mines Department at Dodoma, who was of course familiar with Zoisite from the Longido area in NE Tanzania. The Bank brothers in Idar-Oberstein also identified the mineral as Zoisite and confirmed them turning a blue colour when heated.

“After the gems were returned from the GIA, Hyman Saul had rough stones cut and took them to Jerome Kessler of Saks Fifth Avenue, but he (Jerome Kessler) felt that selling the stones was not the right direction for the store. Hyman Saul then took the stones across the road to the president of Tiffany & Co. The chief gem buyer for the company at the time was the great grandson of Louis Tiffany, a man called Henry Platt. When Platt saw the stones he immediately saw the potential.” The stone was subsequently called tanzanite (named by Henry Platt after the young Republic of Tanzania where it was sourced) and widely marketed by Tiffany & Co. The stone was officially introduced to the world at a grand fanfare at Tiffany & Co. in 1968. Excitement during this initial period ran high and Tiffany & Co. even called it the “gemstone find of the century”. The famous jewelry firm declared it to be the most beautiful stone discovered in the last 2,000 years.

Other gem dealers were calling the gemstone different names. Julio Tanjeloff from Argentina tried calling it Tanjeloffite and it even featured on the cover of the Mineral Digest Volume II in 1971 under this name. But with the marketing clout of Tiffany & Co., the name Tanzanite was soon widely adopted.

The above account illustrates the fact that attributing the “discovery” of tanzanite to a single person or entity is artificial. Are the true “discoverers” the Maasai tribesmen, the Maasai warrior suggesting the commercial value, the Village Chief showing it to mr. Ngoma who failed to act timely to commercialize the find, mr. de Souza who realized the potential value of the stone and handed them to Dr. John Saul for analyses, the actions of mr. Hyman Saul in New York, the Tanzanian Geological Survey Mines Department, the G.I.A. or the Bank brothers who had them analyzed and recognized it as a V-rich variety of Zoisite or Henry Platt of Tiffany & Co. who led a marketing campaign for the stone? If one event was not followed by the next, the gemstone would probably only have been “discovered” much later.

What can unequivocally be stated is that the determination and insight of all these men led to the introduction of a magnificent gemstone, formed by unprecedented natural events starting 585 million years ago and culminating in the human world in 1967.

Mining.

After receiving his license to officially mine the grounds, de Souza began a small-scale mining operation. The operation was plagued by problems from the start. De Souza lost 40% of his claim to rivals, security was a major issue and lack of proper equipment was challenging. De Souza entered into a partnership with a mine owner named Ali Juu ya Watu (Fig. 5), and shortly after they were joined by a certain Papanicholau, a Greek army officer. This partnership was short-lived, ending in acrimony and court action.

By this time other operators became active in the area and Ali Juu ya Watu became a principal role player in the tanzanite operations.

In 1971, disaster struck when government authorities simply nationalised all claims! Manual de Souza died in a car accident and although a local newspaper confirmed his role stating “The Hero of the Tanzanite Rush Dies”, he never experienced the success he so much deserved as the principle entrepreneur. As befitting a gemstone of tanzanite’s stature its discovery will always remain somewhat blanketed in controversy and a history including tales of personal hardship and perseverance.

The complicated yet fascinating geological history as described in writings to follow, seems to be mirrored by tales of political upheaval, marketing problems, price fluctuations and unreliable production followed by periods of relative stability and prosperity for its producers.

Turbulent Times.

From April 1968 to early 1969, seventy eight (78) small prospecting/mining claims were allocated by the Tanzanian government. Private prospectors and local miners subsequently worked the deposit until 1971. During the period from 1968 to 1971, Ali Juu ya Watu, a Tanzanian farmer and entrepreneur, started larger scale mining operations in the area now known as Block C. He apparently produced between 200 and 400 kg of gem-quality tanzanite from approximately 28 000 tons of rock (Davies and Chase, 1994). The main tanzanite bearing ore-zone has been named after him, the JW-zone (short for Juu ya Watu Zone).

Following the nationalization of the mines, nearly three decades of poorly planned and poorly regulated mining activity followed. During the 28 years from 1971 to 1999 the tanzanite deposit was in serious jeopardy of being ruined for future mining due to ineffective government policies and uncontrolled illegal artisanal mining activities. The hard earned tanzanite brand was effectively reduced to an obscure, little known gemstone in a remote location in Africa.

Although the government wielded legal control, it lacked the knowledge and adequate human resources to operate the mines competently. The gemstone mines, including the Merelani mines, were placed under the control of a government owned company called Tanzania Gemstone Industries (T.G.I.). In 1972, the State Mining Corporation (STAMICO) took over control of T.G.I. During the period 1972 to 1976 only approximately 125 kg of tanzanite was recovered (Haule et al., 1978). The Merelani area was under government control until 1983 when the government started its transition period toward privatization. Eventually, it returned ownership to private businesses. The deposit subsequently lay abandoned until 1986 when illegal artisanal miners started moving into the area. In 1989, SAMAX Ltd. reported approximately 30 000 illegal miners on the deposit, mining in a haphazard and dangerous fashion. Prices of tanzanite fluctuated wildly with the changes in political climate, reaching $1,000 a carat in 1984, and bottoming out at around 40 per cent of that in the mid-1990s.

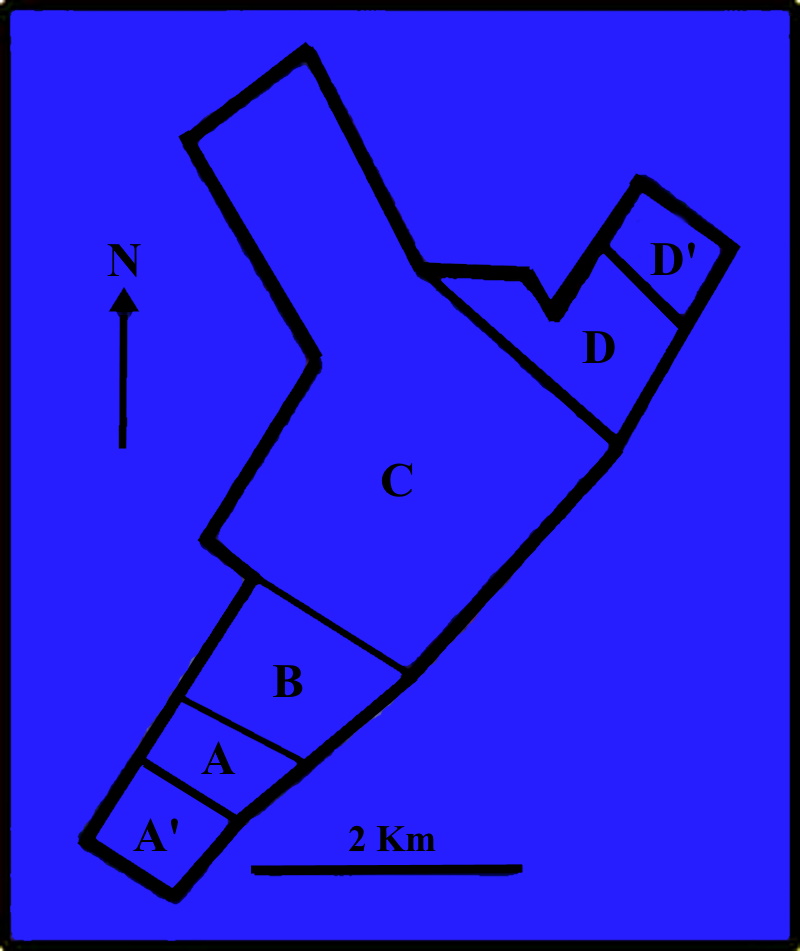

In 1990, the Ministry of Home Affairs cleared the area of illegal miners and subdivided the area into four main mining areas or Blocks (Fig.8).

In July, 1987, the Tanzanian Government floated the tenders for developing tanzanite mining blocks A, B, C and D. J. S. Magezi and Sons Ltd. won the tender to develop block C. Block B was issued to Building Utilities Ltd. and block D to Mfahamiko Mining Company Ltd. The escalation of illegal mining activities on the area made it impossible for the tender winners to enter into their properties. This resulted in the Government cancelling the tenders for consideration of artisanal mining. In 1988, tenders were yet again awarded and J.S. Magezi lost block C during this tender process. Block D extension (D”) was issued to J.S. Magezi and Sons Limited as a compensation for losing Block C.

Privatization, Marketing and Knowledge.

The period 1996 to 2012 saw dramatic changes to tanzanite mining and marketing. Through private companies the general public was made aware of the exceptional rarity of the gemstone by intensive marketing campaigns whilst at the same time the geology of the deposit was investigated in much detail.

Block C, the largest of the five Blocks comprising an area of 8 km2, was awarded to Graphtan Ltd. of London, a company bought over and managed by the U.K. – based SAMAX Ltd. The mining license was administered and worked conducted as a joint venture between Graphtan Limited of London, Africa Gems (also from the UK) and an organization named Tanzania Gemstone Industries (T.G.I.). Whilst Graphtan Ltd. focused on extracting graphite, T.G.I. handled the recovery of the gemstones and Africa Gems took care of the marketing. Graphtan Ltd. predominantly focused on mining graphite and only started a tanzanite evaluation – drilling project on Block C in 1996. This may be seen as the first attempt at formal exploration of the deposit. By the end of 1996, Graphtan Ltd. ceased its operations and was liquidated in mid-1998.

At the end of 1998, AFGEM Ltd. conducted a preliminary investigation and subsequently entered a bid for the Block C mining license. In July 1999, AFGEM Ltd. was awarded the mining license after submitting the highest tender. The Company was listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) in August 2000. The vision, passion and business skills of an individual, mr. M. Nunn and his wife Candice together with an excellent marketing team re-introduced Tanzanite to the world. Mr. Nunn became CEO of AFGEM Ltd. in wake of the Tanzanian government’s change of strategy in returning ownership to private business. During the period 1999 to 2006 the tanzanite brand was intensely marketed and the gemstone regained worldwide popularity, to the extent that it was named the birth stone for the month for December in 2002, joining turquoise and zircon. The gemstone reached an historical high average market value in 2012.

AFGEM Ltd. (and subsequently TanzaniteOne Ltd.) through the insight of its CEO, contributed immensely to the understanding of the tanzanite deposit by sponsoring academic research with a practical application. Through the work of students B. Olivier, R. Gessner, A. Cunningham and mine geologists such as F. Rutahindurwa and many others, a firm academic foundation for the formation of tanzanite and the geological parameters controlling its deposition was established.

The Ph.D. thesis obtained by B. Olivier (2006), is to date the standard reference on many aspects related to tanzanite and its formation. The practical application of the academic work to mine scale is credited to Olivier (who eventually became CEO), and many others during the period 1999 to 2012. Knowledge on the deposit increased exponentially and AFGEM strived towards operating the most advanced gemstone mine in Africa, based on scientific knowledge, to ensure the optimum mining methods and value adding mechanisms to a gemstone that became increasingly popular. The work conducted and applied by AFGEM Ltd. followed by Tanzanite One Ltd. is till this day responsible for the bulk of understanding of the tanzanite deposit and applied by many medium and small scale mines operating in the area.

In following years tanzanite mining was conducted by a variety of private companies operating on various scales of operation. Ownership of land changed from one company to the next in rapid succession rendering a clear event – line complicated.

In Block D extension, the northern most section of the tanzanite mining area (Fig.8) a gemstone Mining License (GML 137/2002) was issued for ten years in 2002 to Capital Zoo Ltd., then transferred to TanzaTanzanite Ltd. in 2003. In 2004 Tanzanite Africa Limited (TAL) became the official owner of GML 137/2002 after completing of a transfer of the license from TanzaTanzanite Ltd. GML 138/2002 was issued for ten years in 2002 to J.S. Magezi and Sons Limited under the Mining Act of 1998. Tanzanite Africa Ltd. currently operates a tanzanite mine under a joint venture agreement with J. S. Magezi and Sons Limited particularly under license number GML 138/2002 on Block D extension. Tanzanite Africa Ltd. conducted intensive drilling on Block D” and based on this operated a medium scale mine based on the operational procedures as established by AFGEM and Tanzanite One for many years.

In 2003, AFGEM Ltd. was bought by TanzaniteOne Ltd., a UK (AIM) listed company, with a market capitalization of 66,5 million British pounds by 2006. TanzaniteOne Mining Ltd. became a subsidiary of Richland Resources Ltd. In 2013, Richland Resources and the Tanzanian Government through the State Mining Corporation (STAMICO) signed a 10 year Joint Venture agreement over Tanzanite One Ltd. On 25th November 2014, Richland Resources Ltd announced that Sky Associates Group Limited acquired all Richland’s tanzanite mining, beneficiation and tsavorite license interests in Tanzania.

The mining area is currently subdivided into six license areas, namely Blocks A extension, Block A, Block B, Block C, Block D and Block D extension (Fig. 8). Formal mining is conducted in Block C and Block D extension, while Blocks B and D are subdivided into mining plots (pml’s) and are being mined by local miners or consortia of local miners. Recently, larger scale locally owned mining commenced in Block A as well.

To read an update on the developments of the mining and other activities on the tanzanite mines from 2001 to 2018, view the excellent summary by Katherine Donahue HERE

During the last few years, Government control on the mining and marketing of the stone became dominant again. Whether the new policy will bring stability and stature to one of nature’s rarest gemstones, only time will tell. It has been 53 years since its discovery.

References.

Davies C., Chase R.J. (1994) The Merelani graphite-tanzanite deposit, Tanzania: An exploration case history. Exploration, Mining geology, Vol.3, No.4, pp.371-382.

Haule, H.I.,Shevchenko, B. and Mwaya, G.T., 1978. Project Report on Merelani tanzanite project. STAMICO, P.O. Box 981, Dodoma.

Olivier B. (2006). The Geology and Petrology of the Merelani Tanzanite Deposit. Unpubl. Ph.D. thesis, Stellenbosch University, 434 pp.

About the Author:

Dr. Reyno Scheepers was involved with the exploration and mining aspects of Tanzanite from 1998 to 2017. He advised AFGEM, Tanzanite One, Tanzanite Africa and numerous medium and small scale miners on the Merelani tanzanite deposits. He supervised several M.Sc. and Honors projects around the gemstone and was the promoter for the 2006 doctoral thesis of B. Olivier. His interest on the tanzanite and related deposits is ongoing.