Article by:

R. Scheepers, G. S. Bitesigirwe, P. Gresse, and H. C. Scheepers

Objectives.

The aim of this communication is to illustrate the multi- source and multi- stage nature of the Proterozoic gold mineralization in the Tanga, Pwani and Morogoro regions of the Republic of Tanzania

Gold mineralization in the region is clearly the result of a long and intricate history of geological events with sources as varied as the Archaean (4.0 to 2.5 Ga) to as late as 0.45 – 0.6 Ma with contributions from continental collision events and related sedimentation, magmatism, volcanism and metamorphism. Several deformation events are fundamental in the understanding of the localization of gold thus obtaining some spectacular enrichment of the metal under specific geological conditions. This is the first in a series of publications to follow on related topics.

Introduction.

The maturity of the Archaean gold deposits in the Republic of Tanzania in terms of their exploration potential was suggested as early as 2012 (Kabete et. al. (2012) and has become a popular narrative due to the lack of the recent discovery of sizeable gold deposits in the Lake Victoria region. The application of innovative exploration techniques may however, still yield success in areas underlain by Archaean lithologies but to date deemed to be of low potential.

In terms of exploration for gold, Proterozoic rocks in the country have traditionally received far less attention than the Archaean terranes. Despite the discovery of the 1.48 Moz gold mine by Shanta Gold, situated in the Lupa gold field in the Ubendian Proterozoic belt, and the ± 780 000 Oz Magambazi deposit in the Usagaran Proterozoic belt, the Proterozoic potential in Tanzania remains underexplored. In this summary we discuss the Au mineralization styles encountered in the Tanga, Pwani and Morogoro regions in Tanzania (Fig. 1) and provide reasons why, in our opinion, the next large scale gold find in Tanzania may well be found in these Proterozoic rocks.

Dunn and von der Heyden (2022) highligted the fact that four gold fields (Mpanda, Lupa, Amani and Niassa) are present in the Ubendian belt and recognized at least three distinct gold mineralization events which are associated with these orogenies (a ∼1.8 Ga event in the Lupa Goldfield, a ∼1.2 Ga event in the Mpanda Mineral Field and a ∼0.45-0.6 Ga event in the Niassa and Amani Goldfields). If anything, the evidence for extended periods of various styles of gold mineralization in the Proterozoic is highlighted by these findings. Gold mineralization in the Usagaran is equally, if not more, complex.

Following on the discovery of the significant Magambazi deposit in the Handeni district, Kabete et. al. (2012) emphasized the importance of the Usagaran belt in terms of gold exploration potential. These authors considered the geographic proximity and “regional strike extension” of the so-called Kilindi – Handeni superterrane to the craton-related Archaean Nyanza Superterrane (2.7 Ga) of significance to gold mineralization. In essence the authors are of the opinion that “Lake Victoria style” gold deposits were present to the east of the Tanzanian craton boundary. These deposits were then subsequently “reworked” (a term that should not exist in geological literature) to create the current Proterozoic gold deposits such as Magambazi.

The Proterozoic rocks experienced at least 1 Wilson cycle post Archaean and as illustrated above at least three orogenic episodes, up to lower granulite metamorphic grade. It would indeed be a resilient “reworked” gold deposit still recognizeable following these episodes. Undoubtedly some of the gold may have been sourced from the Archaean, as would some of the gold be sourced from the extensive later episodes of intrusion, volcanism, weathering-and-sedimentation, and metamorphism.

In addition to the episodes of deformation and metamorphism over a period of more than 1 Billion years of geological history, deformation and metamorphism associated with the Mozambique belt add at least three more episodes of deformation of Upper amphibolite and Lower granulite facies metamorphism.

The Mozambique belt was subjected to four tectonothermal events at 830 – 800Ma; ~760ma; 630 – 580Ma and 560 – 520Ma. All except the last attained upper amphibolite / granulite grade. The chances of finding an Archaean zircon in the Proterozoic rocks adjacent to existing gold mineralization do exist, as these may have survived the metamorphism intact, however, any Archaean gold deposit would not only have been “reworked” but completely obliterated and the remnants displaced over vast distances and depths.

Mykhailov (2018) describes the Mazizi deposit occurring approximately 26 km to the NE of Morogoro in a terrane consisting of a wide (4 – 5 km) shear zone within gneissic, granite – gneiss and migmatitic rocks. The deposit occurs as a steeply dipping (70 – 75° in the northwest) mineralization zone that is extended in the northeast direction (50 – 60°) over 450 m. It is 50 – 70 m wide containing gold grades of up to 40 – 80 g/t (Mazizi Gold Mine Company). Mykhailov (2018) then continues to describe the “newly discovered” Mananila deposit 2.8 km to the west of the Mazizi deposit. He characterizes the host rock to the gold deposit as pinkish – grey gneisses (to migmatites) and amphibolite gently dipping (20°) in a direction of 110 to 130° (ESE). The main mineralization zone is characterized by intensely bleached and sheared migmatites, gneiss and amphibolites cut by en echelon systems of quartz veins striking mainly northeast. “These veins form stockwork systems with veins and veinlets striking to the northwest (310–320°). Sometimes steeply-dipping bodies of quartz breccia that show strikes to northeast and northwest and thickness reaching 1.0–1.5 m might be found” (Mykhailov (2018). The average gold content reportedly ranges from 2 to 3 g/t and the suggested gold content is 20 t based on two trenches.

The above description pertinently summarizes the complexity of the geology, the wide range in lithologies and the structural events in ONE of the gold deposits in the region! As illustrated below, many more styles of gold mineralization are evident.

The Kabete (2012) model has been challenged recently (Stephenson 2025) opting to characterize the gold mineralization in the Dodoma, Morogoro, Handeni – Magambazi area as Sediment Hosted Vein deposits (SHV deposits). Stephenson (2025) puts forward arguments (amongst them isotopic data) for the lateral accretion of the eastern Tanzanian Proterozoic crust. He thus suggests an accreting sequence of oceanic island arcs and sediments being metamorphosed and thrusted against the Tanzanian craton.

This model is in essence what we observed during investigation of several gold mineralized sequences in the region. If the model of Stephenson (2025) is viewed against the standard definition of a SHV deposit where gold is found within quartz veins that are hosted by shale and siltstone sedimentary rocks, he apparently suggests the major accumulation of gold took place during low grade metamorphism associated with accretion. Stephenson (2025) recognizes three possible gold accumulation scenarios for SHV deposits namely a disseminated type, a vein type and a breccia type. He then sites the Mazizi deposit as an example of a breccia type SHV deposit.

It is however difficult to envisage a SHV – type breccia system remaining intact during several episodes of high grade metamorphism. Is the assumption that the “shear zone over intensely leached and schistosed migmatites, gneisses, amphibolites, penetrated by en echelon systems of quartz veins and veinlets, steeply dipping bodies of quartz breccia up to 1.0 – 1.5 m thick…” developed during shear zone formation accompanying a late stage of brittle deformation? Is it then still classified as a SHV deposit, specifically in view of the surrounding rock types?

In this document we put forward evidence that the gold mineralization in the Tanga – Pwani – Morogoro region may be classified as primary structurally controlled Proterozoic lode gold deposits with a variety of, but locally specific, lithological controls. We suggest that gold deposits in the region are characterized by differences in primary origin of gold as well as specific sets of structural, lithological and sequences-of gold-mineralization events that may differ from occurrence to occurrence.

Regional Setting.

The Tanga – Pwani – Morogoro region includes the Handeni district and is situated in the Palaeoproterozoic Usugaran/Ubendian Metamorphic Terrane of Tanzania, along the northern extension of the north-trending Proterozoic Mozambique Mobile Belt. Kabete et al (2008) interpreted the region to comprise a metamorphosed/overprinted eastern extension/remnant of the Lake Victoria cratonic greenstone belt.

This theory is somewhat controversial and has recently been questioned by Stephenson (2025). The geology of the Handeni area is undoubtedly poorly defined and the protoliths are uncertain since it is characterized by highly metamorphosed and migmatized gneissic assemblages including biotite gneisses with hornblende, garnet and pyroxene, migmatitic augen gneisses with garnet, hornblende and pyroxene; quartzo-feldspathic gneisses with hornblende, biotite and pyroxene and pyroxene granulites with hornblende, biotite and garnet. These rock assemblages have been deformed to the extreme, adding to the complexity of the regional geology.

Structural Setting.

The terrane was initially deformed and metamorphosed during westward (cratonward) compression, folding and thrusting causing a near-horizontal fabric parallel to the sedimentary layering and the formation of paragneiss. Related folds and stretching lineations plunge NE indicating large scale westerly attenuation and sheath folding during thrusting. This package was subsequently imbricated with allochtonous volcanosedimentary and ophiolitic packages from the east. Subsequent phases record further progressive shortening in the same direction ending in NNW (mainly sinistral) ductile shearing. The region is located in an area where tectonic overprinting resulted in a number of refolding events with both NW- and NE-trending fold directions.

The fundamental structural framework is linked to an orogenic system comprised of at least two westward- (cratonward-) directed fold-thrust events overprinted by a late NE-trending fold phase. Older ductile structures were continuously reactivated and re-deformed by younger ductile-brittle events developing sheath folds during F2. Thrust zones (mega-breccias?), axial planar refoliation and late shear and fault zones provided channel-ways and conduits for mineral-bearing fluid transfer from deeper levels to higher level ductile-brittle trap structures. Evidence for fluid migration and associated alteration processes is ubiquitous.

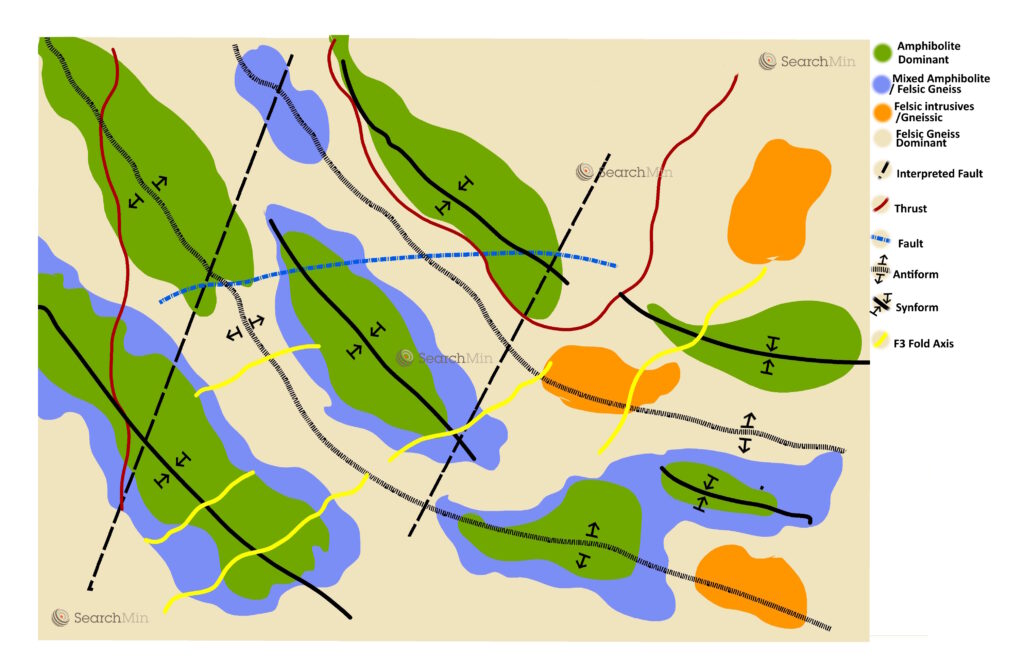

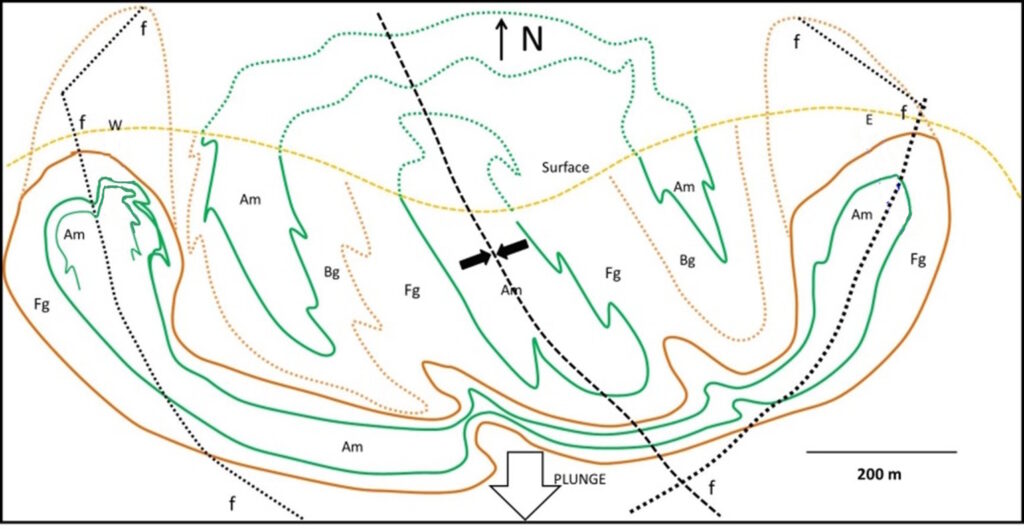

Outcrop-derived foliation trends and dips confirm that the closed sheath folds are synformal structures and the intervening areas composite antiformal structures (Fig. 2).

Amphibolitic assemblages dominate synformal domains, and quartzo-feldspathic assemblages antiformal domains. Despite the apparent clear separation of the two assemblages their margins are tectonically interleaved.

Fig. 2: Diagrammatic representation to conceptualize the geological features typically encountered in an area of approximately 2000 km 2 in the area under discussion. Dominantly felsic gneiss terranes with anticlinal and synclinal amphibolite-dominated sheath folds, often rimmed by a mixture of felsic gneiss and amphibolites are typical.

Detailed mapping shows that the complex internal smaller fold features representing second or third order structures are related to the large scale features but are also related to intricately refolded older tight folds (and thrusts?) belonging to earlier deformation events.

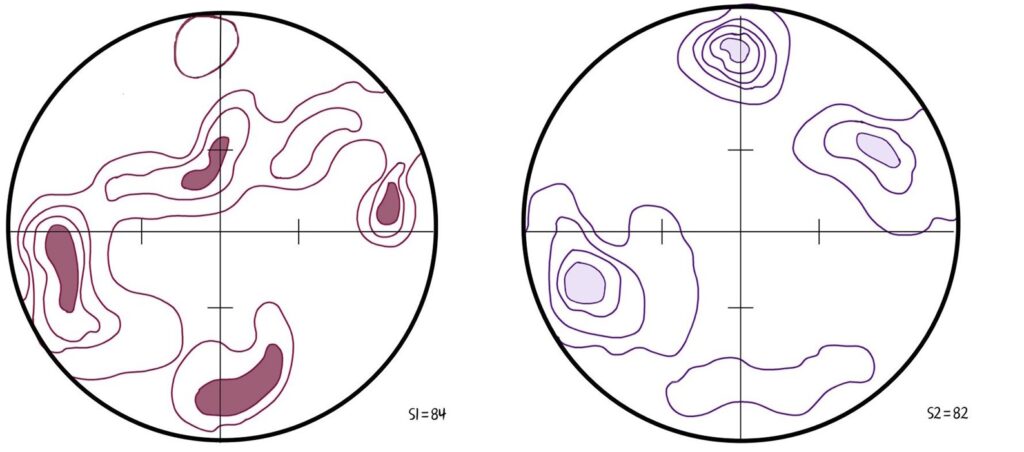

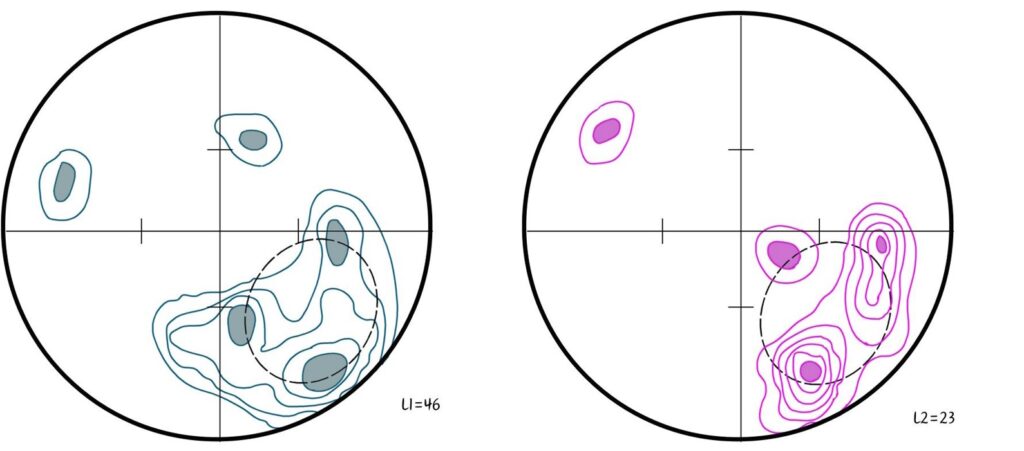

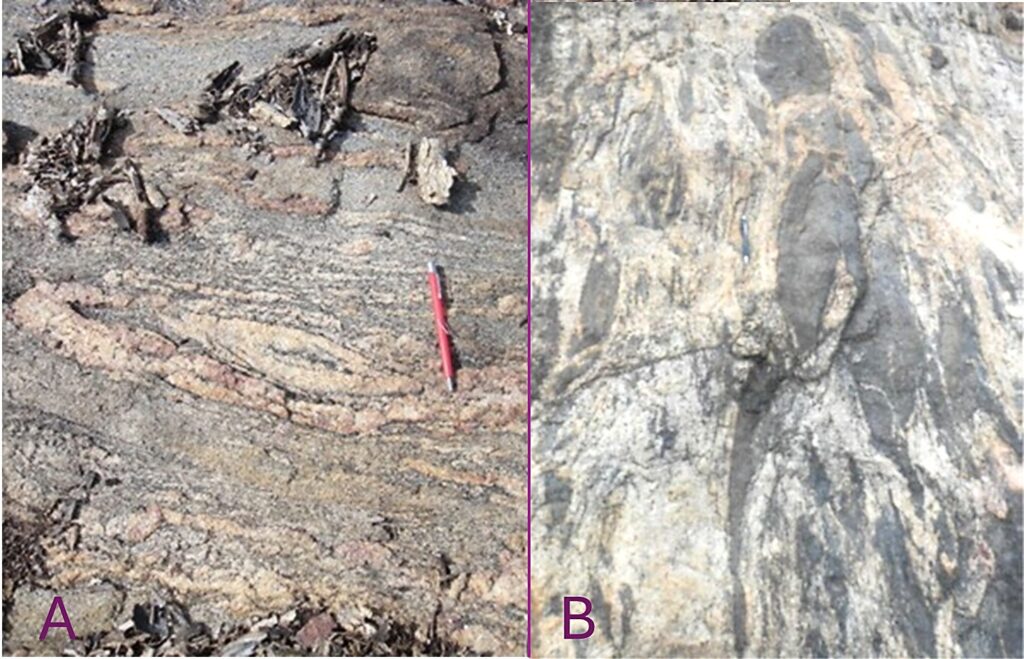

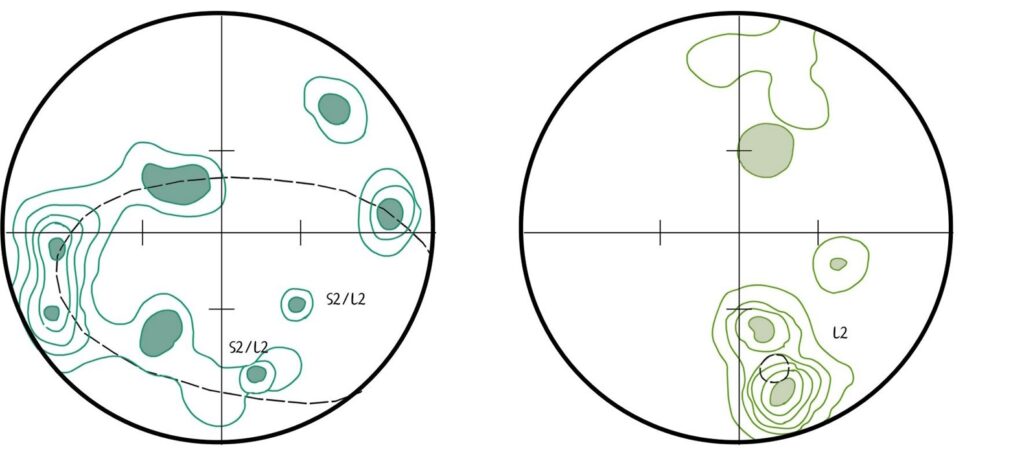

Stereographic analysis of measured structural elements clearly shows the dominant NW-trend of foliations S1 and S2 (Fig. 3a, b). The oldest visible ductile foliation S1 is folded by F2 ductile-brittle folds with axial planar foliation S2 which parallels S1 outside F2 fold hinges. F1 and F2 fold axes as well as mineral stretching lineation L1 and mineral intersection lineation L2 define a maximum in the SE quadrant of Fig 4a, b (L2/B2 = 133°/37°), indicating the major fold orientation and F1 thrust/mass transport direction (SE to NW). The fact that fold axes and lineations of both visible deformation events are sub-parallel and also coincided with the S1 stretching lineation suggest continuous folding and transposition to the NW with fold axes rotating towards the stretching direction to form sheath folds. These structures also occur on outcrop scale (Fig. 5).

Figure 3. a. Left – Regional structural trend of S1 foliation; b. Right – Regional structural trend of S2 foliation. (Equal area, S1 = 84 measurements, S2 = 82 measurements).

Fig. 4: a ) Left – Regional L1/B1 trend; b) Right – Regional L2/B2 trend (Equal area, L1 = 46 measurements, L2 = 23 measurements)

Fig. 5. Left – Sheath folding in quartz-feldspar-biotite gneiss. b. Right – Typical disrupted F2 fold in mixed amphibole / quartz-feldspar gneiss

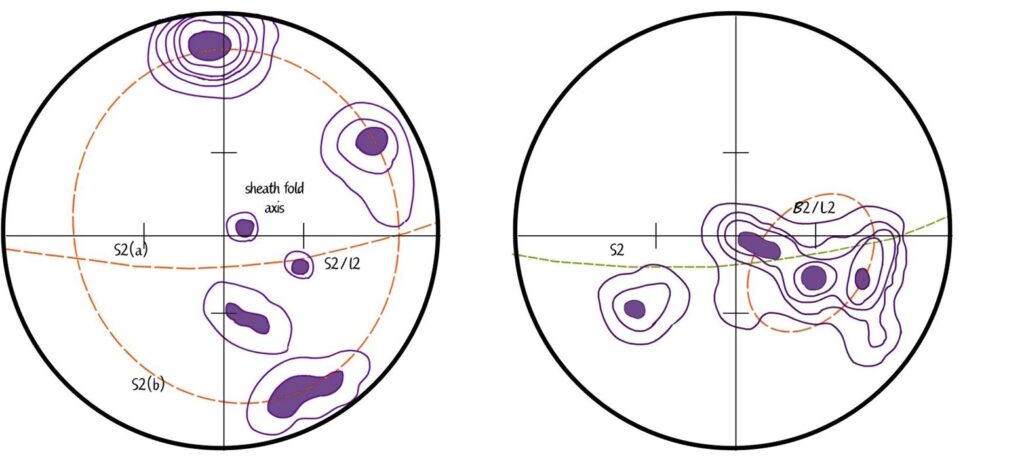

Foliations in specific synforms define a small circle distribution representing a mega-sheath fold plunging to the SE (L2/B2 = 163°/21°; Fig. 6). The derived sheath fold axis coincides with local and regional linear elements. Other major structures in Fig. 2 are of the same style. The sheath folds are also partially the product of NE-trending cross-folds intersecting NW trending F1 folds (Fig. 2).

Figure 6. Stereographic geometry of a singular sheath fold; a. Left – planar elements; b. Right – linear elements. (Equal area, S1/S2 = 35 measurements, L2/S2=29 measurements).

On a more local scale (mine scale) foliations and lineations /fold axes similarly may define a sheath fold geometry plunging somewhat more steeply E to SE (B2/L2 = 114°/48°; Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Stereographic geometry of part of a mine scale synformal sheath fold; a. Left –planar elements; b. Right – linear elements. (Equal area, S1/S2 = 22 measurements, B2/L2 = 21 measurements)

The latest (F3) folding event is evident as late chevron style folds, only evident in some location (Fig. 8)

Fig. 8: Late (F3) chevron style folding.

The regional structural elements as discussed above plays a dominant role in the location and style of individual gold mineralized showings in the region. The specific style of each deposit is however, also controlled by lithological as well as other gold mineralizing controls as discussed below.

Gold Mineralization.

Genesis and structural controls on gold mineralization are of paramount importance for exploration in orogenic lode gold provinces. The presence of duplex thrust-fold systems is the main prerequisite for significant mineralization to occur but subsequent shear systems linking these to anticlinal or domal features higher up in the sequence is as important in order to focus and trap gold-bearing fluids. On local scale lithological control and clear competency and chemical contrast is a further focussing requirement. Non-permeable cap rocks and anticlinal features prevent fluids from escaping upward and disseminating in upper stratigraphic units.

The region under discussion appears to meet all the requirements of a classic Proterozoic lode gold province. The fundamental structural framework is linked to an orogenic system comprised of at least two westward- (cratonward-) directed fold-thrust events developing sheath folds during F2, overprinted by a late NE-trending fold phase and late F3 crenulation folding evidenced in some locations. Older ductile structures were continuously reactivated and re-deformed by younger ductile-brittle events. Thrust zones (mega-breccias?), axial planar refoliation and late shear and fault zones provided channel-ways and conduits for mineral-bearing fluid transfer from deeper levels to higher level ductile-brittle trap structures. Evidence for fluid migration and associated alteration processes is ubiquitous, as described above. Competency and chemical contrast between amphibole gneiss and quartz-feldpar-biotite gneiss appear to have provided a suitable lithological trapping mechanism. Shear zones and zones of intense axial planar refoliation provided further suitable permeability for fluid migration and entrapment.

In order for any economic gold deposit to have developed anywhere in the region under discussion suitable trap sites need to have developed. Trap sites are provided by competency contrasts, confining structures and non-permeable cap-rocks.

The main lithological control has currently been established as the interleaved, transitional contact zone between amphibole- and quartz-felspar-biotite gneiss. These contact zones are found all along the margins of the major antiformal and synformal structures as well as in fold closures where these are preserved.

The primary structural control will be antiformal (domal) features which trapped upward migrating gold-bearing fluids. Within these, low-stress zones such as antiformal hinge zones (saddle reefs), intensely refoliated (S2) axial planar zones of antiformal folds, second- and third-order folds, antiformal sheath folds and syn-late shear zones, faults, quartz veins and pegmatites will provide local focus points. Individually these trap sites are normally too small and isolated to develop a deposit of mineable dimensions. Operating Proterozoic lode gold mines all show a combination of these features forming a linked network of mineralized features over large vertical and horizontal distances (up to km scale and more).

The role of early mega structures.

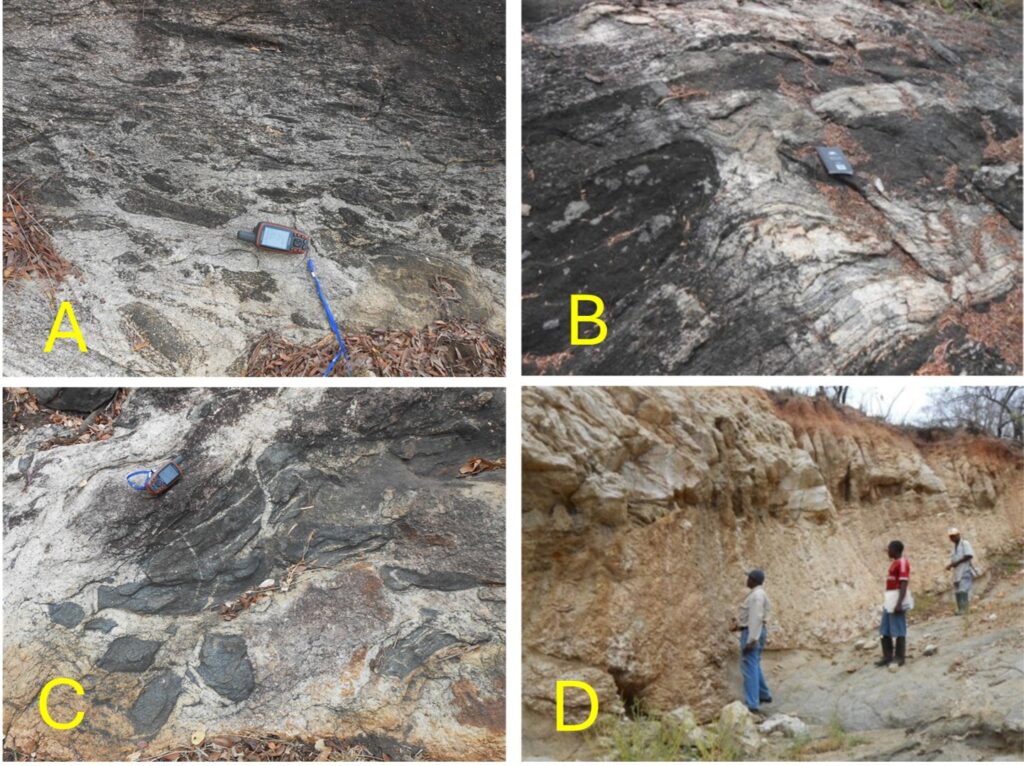

S1/S2 in interleaved (mixed-) quartz-feldspar-biotite gneisses and amphibolites (this mixture itself is probably a product of F1/F2 isoclinal folding and transposition) often shows the development of mega-breccias or tectonic melanges (Fig.9a) thought to represent large tectonic slides or thrusts of a deep-rooted ramp-style duplex system probably causative to both fold-thrust events described.

Fig. 9 a. Left top – Mega-breccia/melange of fragmented amphibolitic units in quartz-feldspar-biotite gneiss matrix; b. Right top – boudinaged amphibolite layer with felsic material wrapping around and filling neck-zone; c. Left bottom – intrusive nature of quartz-feldspar-biotite material into brecciated amphibolites; d. Right bottom – quartz-feldspar-biotite pegmatite intruding leucocratic granite of the same composition.

These melanges, boudinage structures (Fig. 9b) and other intense foliation-parallel shear zones show extensive quartz-feldspar+/-biotite veining, often clearly intrusive (Fig. 9c), suggesting that these major shear structures were conduits for fluid transfer from deeper levels late (syn/late F2) during the deformation history of the area. Some of these fluids may even be intrusion-derived as massive quartz-felspar-biotite pegmatites (Fig. 9d) intrude granites of similar composition.

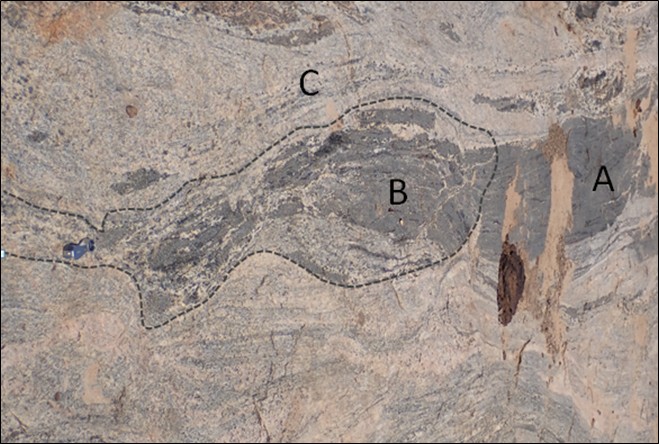

The repetative nature of deformation and fluid/rock interaction during this deformation stage is evident in Fig. 10. Solidified fine grained amphibolite (A) interacted with and was displaced by felsic fluid/melt (B) which was displaced by later fluid/melt (C).

Fig. 10: Fine grained amphibolite (A) displaced by and interacted with felsic melt (area B) and later felsic fluid / melt (C).

These thrust zones ( with or without mega-breccias) together with S2-axial planar refoliation and late shear zones provided conduits for fluid transfer from deeper levels to higher level ductile-brittle trap structures.

Although a lack of timing constraints (age determinations) places a question mark on the timing of an event described below involving early Si, K, Na and to a minor extent Ca fluid influx, the physical evidence is abundant. Rock units of up to 200 m in strike length and from 2 to 12 m in width are present in the core of sheath folds and specifically entrapped in the fold closures of F2 anticlinal and synclinal structures. These rock units consist of ±30% Richterite, ±30% Quartz, ±20% Pyroxene (Mg, Fe), 10% Aegerine, ±4% Actinolite, ±4% Wonesite and ±2% Tremolite. In places these early assemblages were cross cut by later shearing and alteration with an increase in K, Ca and Na content.

Gold enrichment during this early phase generally accompanies the contact zones of the felsic quartz-feldspar+/-biotite ductile zones and the amphibolitic units. Importantly, the gold is often not in the brecciated/boudinaged amphibolite, but in the felsic ductile component. This may be an indication of remobilization of gold during felsic intrusion at deeper levels accompanying early deformation (F1).

Gold mineralization during early (ductile and zones of brittle deformation) conditions.

This mineralization style is predominantly encountered in the hinge zones of the antiforms and synforms in the region (Fig. 2). The hinge zone is normally also transected by a number of axial planar shear zones which slice up the garnet-amphibole gneiss into a number of discrete, elongated tectonic segments or slices, the latter leading to a different mineralization style as discussed below. The association of tectonically segmented garnet-amphibole gneiss with mega-axial shear zones within an antiformal hinge with high pressure alteration is regarded as an exceptionally favourable location for significant gold mineralization within a combination of possible trap sites.

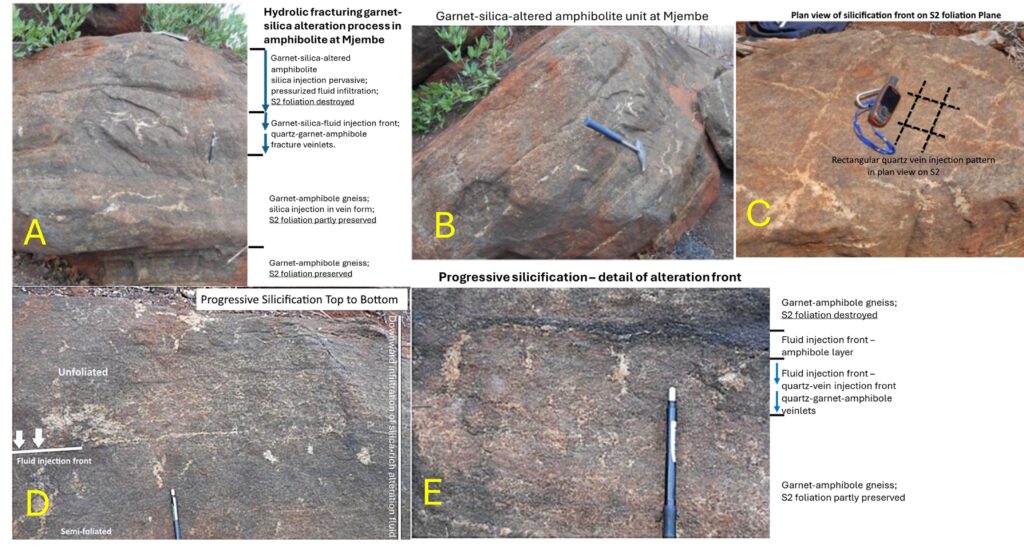

The silica-garnet alteration process of amphibolite as seen in published pictures of drill core from various locations is also exposed in outcrop. Stacked units of garnet-silica-altered amphibole gneiss display features of systematic alteration by means of silica-garnet-amphibole-producing fluid injection (Fig. 11 a). It appears that fluid infiltrated individual units downward (current position) from layer-parallel fluidized shear surfaces through a process of tectonic over-pressure and hydrolic fracturing. Altered layers show systematic destruction of foliation from the top down with replacement of the foliated rock by a massive, silicic-garnet-quartz-amphibole rock (Fig. 11 b, c). This rock type is the main persistent gold carrier in several gold showings in the region suggesting that the alteration fluid also carried Au and sulphides. At the interface between altered and semi-altered amphibolite (‘injection front’) quartz veins penetrate vertically down (current) into the underlying material suggesting a kind of hydrolic fracturing process injecting fluid downward (current) into the layer (Fig. 11 c, d). On foliation surfaces this fracture pattern is rectangular (Fig. 11 e).

Seen in regional context it can be speculated that silicic gold-bearing alteration fluids infiltrated amphibole gneiss layers through a process of thrust – duplex – induced tectonic loading giving rise to above – normal fluid pressures. On a layer scale fluids appear to have been introduced along layer-parallel shear surfaces with the associated tectonic overpressure forcing fluids down into individual layers through a process of hydrolic fracturing and vein-injection.

Fig. 11 a. Top Left: Complete silica-garnet-altered unit showing silica-fluid infiltration and alteration with loss of foliation from top to bottom; b. Top middle: Side-view of same unit clearly showing upper quartz-matrix-infiltrated garnet-silica amphibolite and lower quartz-vein-injected, partly foliated garnet-amphibole gneiss; c. Top right: Plan view (S2) showing rectangular silica-injection vein pattern. d. Bottom Left: Detail of suggested silica-injection alteration ‘front’ with amphibole layer; e. Bottom Right: Detail of suggested silica-injection alteration ‘front’.

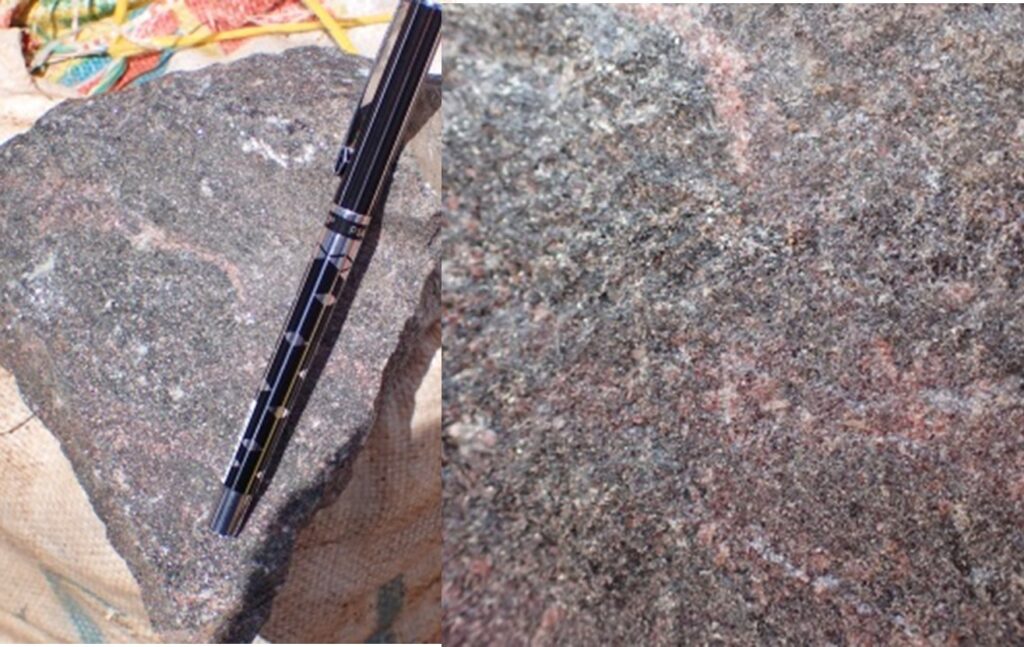

This kind of mineralization / alteration would have formed in high-pressure regimes in rock assemblages underneath ramp duplexes. A typical example of ore of this type being mined is shown in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12. Example of silica-garnet “replacement” ore illustrating gold and sulphide enrichment during early ductile conditions. In some places fluids related to brittle deformation enriched the primary ore (see below).

According to the classic lode gold model fluids would rather migrate to areas of low strain such as hinge zones of overlying ramp – antiforms, late reactivation structures and cross – cutting shear zones, etc. It can therefore be argued that replacement gold mineralization in stacked alteration units may be of low tenure and that associated high – tenure mineralization will only occur in reactivation zones such as re-foliated zones, late shear zones and other late fractures and faults, exactly what is observed throughout the region.

On a mine scale (Fig. 13) the following is observed with regards to this mineralization style:

- The silicification process evident in outcrops, clearly remobilized gold associated with ductile deformation and silicification as is evident on a regional and mine scale. Gold contained in these silicified zones add to the background gold grade in silicified ± garnet amphibolite with an average background concentration of 1 – 2 g/t (up to 3 to 4 g/t in places). On some mines gold is particularly closely related to a highly silicified garnet rich zone.

- The massive silicified ± garnet amphibolite within high pressure ductile to brittle condition zones is cross – cut by later brittle condition reactivation, such as refoliated zones, late shear zones and other late fractures and faults as is described below.

- The silicification episode is most likely coeval with some early sulphide enrichment, the first of many sulphide enrichment episodes under various conditions from early ductile to late brittle conditions. Evidence for this is ample from core drill data (Handeni Gold Inc. 2010 – 2011, various presentations and news releases).

- It is evident that there is not a single source of gold during this episode but multiple source materials from ultramafic, to mafic and felsic. The age of these sources are most likely ranging from Archaean to Early Proterozoic (Andean type subduction) and Late Proterozoic (Intermediate and Felsic magmatism).

Fig. 13: a) An example of the typical pattern of rectangular quartz veining perpendicular to S2 in massive silicified garnet amphibolite from a gold producing mine shaft. b) Massive silicified garnet amphibolite within a gold producing mine shaft with S2 destroyed (bottom half of photograph). Note the pattern of early quartz stringers, rarely containing visible gold. A late, brittle condition, shear fracture filled with quartz, often containing visible gold, is evident in the top half of the picture, illustrating two distinct and time/condition-separated mineralization events.

Gold mineralization associated with early brittle deformation.

On a regional scale this is an important contributor to gold mineralization. The mineralization is locally controlled by boudinaged layers consisting of quartz boudins with either felsic gneiss or amphibolitic layers wrapping the boudins (Fig. 14). Gold is concentrated in boudin necks and occasionally within fractures in boudins.

Fig. 14: Looking down bedding dip illustrating boudinaged gold bearing quartz vein along plunge direction. Red pencil for scale. Note later shearing of the boudinaged layer with secondary quartz vein.

Gold mineralization and the F2 folding event

A significant percentage of the gold currently mined in the region is undoubtedly controlled by the F2 fold event and the deformation related to this event (Fig. 15). The combination of F1 deformation followed by F2 created a complex gold distribution pattern, differing from location to location. In the example below (Fig. 15) a southerly plunging synclinal sheath fold with thinning of a garnet amphibolite along the syncline axis and thickening on the limbs is illustrated. Thickening and thinning of the garnet amphibolite in the interconnecting bottom of the synclinal structure, most likely sheared away, is evident in many cases.

Gold is concentrated in the zones of thickening of the amphibolite on the sheath fold limbs and within the F2 fold axis on the sheath fold limbs. Examples of the same situation within anticlines are known and in some instances gold is concentrated within felsic gneis/ amphibolite units in the thickened sheath fold limbs.

Fig. 15: Diagrammatic cross section of a typical sheath fold closure plunging to the south. Top section of the sheath fold is removed by weathering. The Western and Eastern limbs of a southward plunging syncline (axis illustrated by dark arrows and trend by black broken line) are illustrated.

It is of critical importance to understand that the F2 folds (as in Fig. 15) terminate in a direction more or less parallel to the sheath fold axis in this case in a northerly as well as southerly direction. A different F2 thickened unit develops subparallel but adjacent to the first unit in a northerly and southerly direction.

Within the zones of thickening F2 folding determines the attitude and location of gold mineralization. The F2 folds are interpreted to be the most significant event reconcentrating gold from the prior silicification event (see 5.2) and reconcentrating it in fold hinges of the F2 event in quartz veins along fold hinges (Fig. 16). As described below the fold hinges also suffered significant (F3?) brittle deformation adding further to gold enrichment.

Fig. 16: Looking down plunge (20°) in the core of an F2 fold subparallel to the fold axis of a sheath fold.

Yellow circle indicate quartz stringers related to the early (see 5.2) silicification event and yellow arrow quartz veins related to F2 gold enrichment along a reactivated shear zone (F3) along partly silicified bedding plane of garnet amphibolite.

Faulting and shearing is closely associated with the amphibolite thickening on the fold limbs and is most likely a primary cause of limb thickening, initially areas of fluid accumulation and eventually alteration along tension zones and eventually fracture zones.

Late stage gold mineralization.

Under increasing brittle conditions the following are interpreted as typical conditions under which gold mineralization takes place:

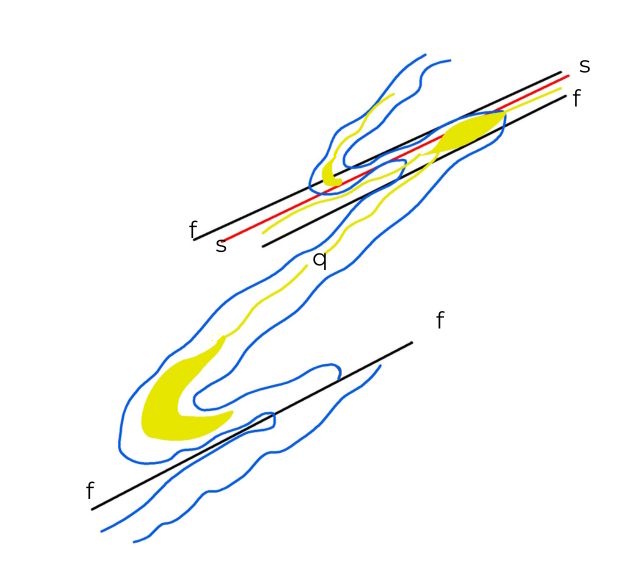

- F2 fold hinge separation from fold limbs creating secondary conduits for gold mineralizing fluids (Fig. 17).

- Axial plane shear zones developed along F2 and F3 fold hinges with increasing brittle conditions creating conduits for gold migration (Fig. 18).

- Regional shear zones within synform or antiform cores mostly in a NNW-SSE (following dominant former ductile shearing directions) or NW-SE direction.

- Regional shear zones in a NE-SW direction post F3 folding including elaborate breccia zones.

Fig. 17: Illustration of fold limb separation from fold hinge creating conduits for Au bearing fluid migration

Fig. 18: Note shearing cutting through fold axial planes (axial planar shearing) (red) and quartz pockets enriched in gold within these shears (yellow)

Summary

In terms of the two currently proposed models for the primary nature of gold mineralization in the region, namely metamorphosed Archaean gold and Sediment Hosted Vein deposits the following can be noted:

Archaean (Lake Victoria) gold deposits are typically related to sequences of mafic to felsic volcanic rocks, banded iron formations (BIF), metasedimentary rocks and granitic rocks commonly with high gold concentrations on contact zones, quartz veins, fractures and structural intersections. Metamorphism of these rocks to upper amphibolite and lower granulite metamorphic grade would undoubtedly remobilize gold and produce a smorgasbord of metamorphic rocks. BIF for instance may produce gneisses containing actinolite, grunerite, hedenbergite and fayalite amongst others. Work to date encountered very little of these parageneses.

Based on the work of Bitesigirwe (2013) the dominant protoliths of the assemblages in the region under discussion are basalts and basaltic andesites. In addition the garnet (almandine) – plagioclase (andesine + oligoclase) + biotite (oligoclase) – quartz and occasionally sillimanite or kyanite suggest assemblages of pelitic rocks of sedimentary origin or sediments from metamorphosed basalt.

The region was subjected to at least one episode of subduction with an addition of mafic, felsic and intermediate intrusive and extrusive rocks and metasediments in what was most likely a back-arc basin. This would create a scenario whereby gold was again introduced to the system.

The bulk of the gold in Lake Victoria gold deposits are contained in quartz veins and pockets. Under the metamorphic conditions and structural deformation as described the following may be envisaged:

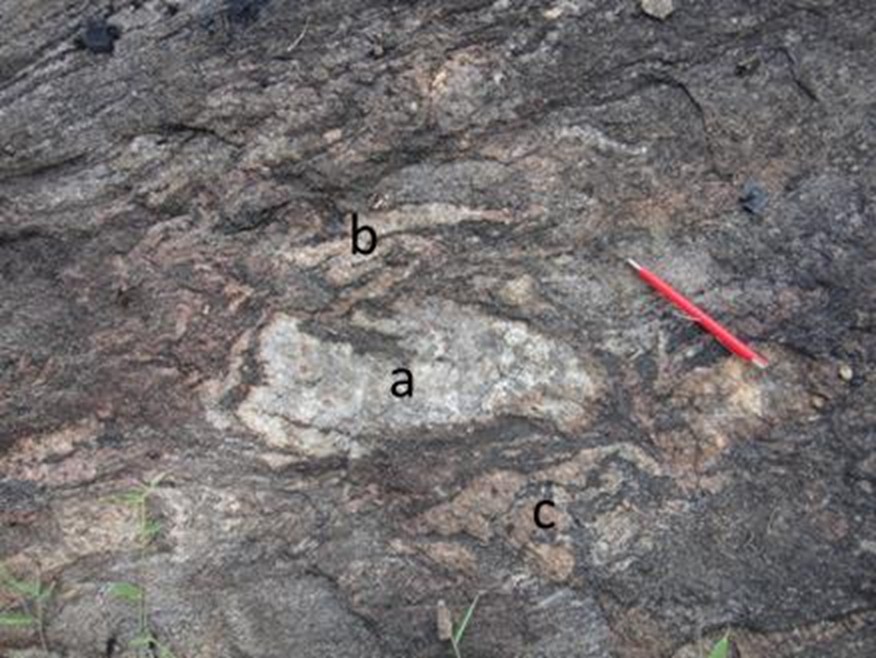

A proportion of the Archaean quartz veins may have survived the metasomatism and hydrothermal alteration accompanying the multiple episodes of intense metamorphism and deformation. These veins may resemble an assemblage such as depicted in Fig. 19 from the region under discussion.

Fig. 19: Potential Archaean quartz remnant (a) in amphibolitic gneiss with deformed secondary quartz vein of younger age (b) and deformed felsic gneiss leucosomes (c).

The bulk of the gold contained in the Archaean quartz veins, shear zones, fractures etc. was remobilized and precipitated under various metamorphic and deformational conditions.

A proportion of the Archaean gold was redistributed in sedimentary packages during weathering and redistributed during metamorphism.

Sediment hosted vein deposits may very well have formed during deposition of siltstones and shales during low grade metamorphism accompanying the West – East accretionary episode as suggested by Stephenson (2025). Supposedly remnants of these mainly quartz vein deposits may have survived the high grade metamorphism and be present as gold bearing quartz veins in felsic gneiss packages potentially as boudins engulfed in ductile deformation zones. A proportion of the gold (specifically disseminated gold enrichment) however, would be redistributed and contained in trap- and contact zones in felsic gneiss and on contact zones between felsic gneiss and amphibolite gneiss.

Conclusion

It is clear that the Proterozoic gold deposits in northeastern Tanzania are sourced from multiple source rocks, have a history of gold enrichment ranging from ductile to brittle conditions and are essentially structurally controlled. They are typical of Proterozoic Lode Gold deposits and exploration models should keep this in mind.

The region is in dire need of investment in terms of academic research on these deposits, specifically in terms of their chemical/isotopic characteristics, protoliths, structural evolution related to very constrained time windows during their evolution and economic viability. Any academic investigation however, should not focus on selected deposits but on various deposits in the region as a whole as they vary dramatically in all geological aspects from location to location.

Dr. Reyno Scheepers can be contacted for consultation via our website or by emailing admin@searchmin.com

References

Bitesigirwe G.S. (2013).https://www.academia.edu/72571599/Gold mineralization in a high grade metamorphic terrane in the Handeni District Eastern Tanzania.

Kabete, J.M., Groves, D.I., McNaughton, N.J., Mruma, A.H. (2012). A new tectonic and temporal framework for the Tanzanian Shield: Implications for gold metallogeny and undiscovered endowment. Ore Geology Reviews, 48, 88-124.

Mykhailov V. (2018). Mazizi Gold Mine Tanzania / https://www.mutusliberint.com/mazizi-gold-mine.

MykhailovV., O. AndreevaO. and OmelchukO. (2020). Model of the new gold deposit Mananila (Tanzania). European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers Source: , Geoinformatics: Theoretical and Applied Aspects 2020, Volume 2020, p.1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3997/2214-4609.2020geo059

Dunn, Stephan C. and von der Heyden, Bjorn P. (2022). Proterozoic – Paleozoic orogenic gold mineralization along the southwestern margin of the Tanzania Craton: A review. Journal of African Earth Sciences, Volume 185, article id. 104400.

Stephenson L. (2025) The Dodoma Morogoro Handeni – Magambazi area, Eastern Tanzania-A Proterozoic Sediment Hosted Vein Deposit. Natural Resources. Vol. 16. No. 4. 95-132. doi: 10.4236/nr.2025.164006.